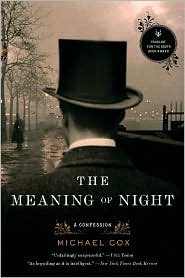

Edward Glyver’s mysterious life unfolds – and unravels – in Michael Cox’s The Meaning of Night: A Confession.

The Meaning of Night: A Confession

Michael Cox (stop giggling)

2006

W.W. Norton & Company

“After killing the red-haired man, I took myself off to Quinn’s for an oyster supper.”

Recent successes such as The Sopranos and Dexter illustrate that a protagonist doesn’t have to be just or admirable to be captivating. The hero needn’t be a hero; and Michael Cox’s man, Edward Glyver, certainly falls short of the title, but he is fascinating to witness. He’s a scholar; a bibliophile; he’s a man of passions. He’s a whoring laudanum abuser; a patron of opium dens; he’s a murderer. And he’s our narrator.

[Killing the red-haired man] had been surprisingly – almost laughably – easy. I had followed him for some distance, after first observing him in Threadneedle-street. I cannot say why I decided it should be him, and not one of the others on whom my searching eye had alighted that evening. I had been walking for an hour or more in the vicinity with one purpose: to find someone to kill. Then I saw him…

The Meaning of Night is Edward Glyver’s personal account of mystery, betrayal, obsession, and madness. Set in Victorian London (with all the trappings), this narrative spans thirty years: Glyver takes us back to his childhood, where we see traces of a vindictive and dangerous nature; lets us in on the shocking secret kept from him by his family; and introduces us to his friend Phoebus Daunt, who is soon to become a formidable enemy.

Supplementing the plot is Glyver’s opiate fueled descent into insanity. Cox’s narrator immediately proves that he is on a par with the novel’s most disquieting villains, and he is as difficult to trust as any of the shadowy characters he encounters. Far from being repellant, however, Glyver is sly and witty, and his lesser revenges upon minor trespassers are somewhat gratifying. Educated, but overconfident in his intellect; experienced, yet often unaware; he is a complex and contradictory character, and an apt guide for this journey through the pretense of Victorian England society.

Michael Cox’s grasp of the genre gives The Meaning of Night a sense of authenticity and not imitation. Presented as publication of a manuscript found in a Cambridge library, it is complete with a pseudo-editor and bibliography of the fictional author Phoebus Daunt. The book is longer than most novels (700 pages) given the time span covered in the storyline, so be prepared: There’s three decades of debauchery to cover; settle in and break out the absinthe. Just steer clear of the Dalby’s (you’ll have to read the book).